Bibliographic Info:

Bibliographic Info:

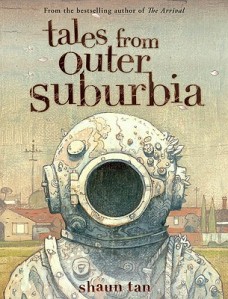

Tan, Shaun. 2009. Tales From Outer Suburbia. New York: Scholastic. ISBN 9780545055871.

Review:

Shaun Tan’s Tales From Outer Suburbia is a book sure to satisfy both graphic novel lovers and readers of short stories. Tan’s illustrations and his stories are whimsical and bizarre, eerie and beautiful. There are many influences here, but Library Journal puts it best: “Chris Van Allsburg meets The Outer Limits” (2009).

Fifteen different stories are presented with fantastic illustrations. Some illustations are in black and white while others are in the muted earth tones that Tan is known for, such as in his wordless book The Arrival. The book’s second story, “Eric”, is both a tale of a foreign exchange student. Or is it an alien visitor? The host family doesn’t quite know what to do with this tiny being who finds more interest and joy in candy wrappers, bottle caps, and the Fibonacci-like patterns present in everyday objects. The gift Eric leaves for his host family is both lovely and magical, yet also very odd.

The story “Undertow” features a dugong, a creature similar to a manatee, that mysteriously appears on someone’s front lawn. The couple who own the house seem to do nothing but fight, which temporarily stops when the neighborhood bands together to try and save the dugong. When the dugong is rescued, rather unremarkably, things appear to return to normal as the neighbors go back to their everyday lives and the couple returns to arguing. There is a poignant moment at the end. “Nobody saw the small boy clutching an encyclopedia of marine zoology leave the front door of that house, creep toward the dugong-shaped patch, and lie down in the middle of it, arms by his sides, looking at the clouds and stars, hoping it would be along time before his parents noticed that he wasn’t in his room and came out angry and yelling” (Tan 2009). The last two sentences, which I will omit here, are quiet and almost apologetically beautiful.

Tales From Outer Suburbia was a 2010 YALSA Best Book for Young Adults, a 2010 ALA Notable Book for Children, and a 2009 Publishers Weekly Best Book for Children, among others. Each story reads like a snippet in a stranger’s life, but perhaps a stranger that reminds you of yourself or someone you remember from long ago. There is no trace of didacticism, although many stories could easily go that way. Instead, Tan leaves imagery, in both his illustrations and his words, to speak how they will to the reader. This book would work particularly well in a writing group of tweens or teens. Before reading any of the stories, have group members write a poem or story based on a single illustration from the book. Afterward, read the original, accompanying story aloud to the group and discuss how experiences and emotions can change interpretation.

References:

Benedetti, Angelina. June 2009. Library Journal. http://ezproxy.twu.edu:2125/DetailedView.aspx?hreciid=|20183934|21534168&mc=USA#. Accessed December 2, 2013.